Introduction

One of the best things about any kind of physical training is that it’s totally honest; you can’t fool your body; there are no shortcuts and no quick fixes. If you try to rush things, particularly resistance training, you will pay the price and get yourself injured sooner or later.

But physical exercise is a broad church and there are many options and many, many ways to do it.

This leads to the lines between different modes of exercise and ways of doing things becoming blurred. When you couple this with people who deliberately mystify things in an attempt to sell their particular brand of training, it gets even more confusing.

The time will come when it’s appropriate to add some flare to your training (if only to add some variety), but if copying random exercises that look cool on social media is your priority, I suggest that you reconsider your approach.

As cyclists, whose priority is performance on the bike (and getting out on the bike as often as possible), the objective should therefore be to complete any off-bike work with the minimum effective dose, using methods that provide the biggest bang for your buck.

There are no cycling-specific exercises and anyone who tells you there is, is bullshitting you…there are, however, cycling relevant ones. What’s clear is that the most effective approach is to build your base by consistently working on getting stronger in fundamental movement patterns. It’s not sexy and can be repetitive, but it’s hands-down the best way to build robustness, minimise your injury risk and improve your performances on the bike.

What Are The Fundamentals?

Fundamental movements are the basic movement patterns we perform as humans. They consist of:

- Squatting – bending down and standing back up again.

- Hip-Hinging – bending forward to pick something up off the floor.

- Upper-Body Pulling – drawing something in towards your body.

- Upper-Body Pushing – pushing something away from your body.

They are all compound movements, meaning that they are multi-joint and therefore utilise many muscle groups in coordination across those joints. They all require effective core control to do them effectively, but I think they are enhanced when supported by specific core training, which resists any movement through your trunk.

The Benefits Of The Fundamental Movements.

Strength training programs based on these four basic movement patterns above (plus bracing for your core stability) offer a host of benefits:

- Time Efficient – working multiple muscle groups over multiple joints at the same time is more effective than doing many single-joint exercises. The combined effect of organising yourself to complete these movements means you improve your coordination, balance, ability to recover and strength at the same time.

- Dynamic Transfer – mastering these basic moves has a direct application to your performance on the bike, as well as your health and wellbeing off it.

- Variety – each move can be scaled in many ways, from beginner to advanced. Each of these can be combined with endless training methods and schemes.

- Robustness – taking the moves through a proper, full range improves your joint health and minimises muscular imbalances, meaning they protect you from injury!

The Cons of the Fundamental Movements.

I think this is the best way to go, but (as with anything), there are some drawbacks to using these fundamental movements as the basis of your strength training plan:

- Repetitive – despite being able to scale and vary the movements in different ways, you are still performing the basic movement over and over again. This isn’t flash and can be monotonous for some people.

- Complex – because these moves are multi-joint, it means that they can be hard to learn and take time to master. During this time, there is a risk that you overextend yourself, push too hard and hurt yourself.

How Do I Do The Fundamental Movements?

Squat

In my humble opinion, the squat – in particular the Back Squat – is the king of all exercises when it comes to the transfer of performance onto the bike. If you improve your squat, there is a direct (although somewhat delayed) improvement in your on-bike performances.

This is likely because it uses similar muscle groups to the pedal stroke, done well it evens out muscular imbalances (very common in cyclists), requires fantastic core stability and requires the hip, knee and ankle joints to move through a full range of motion.

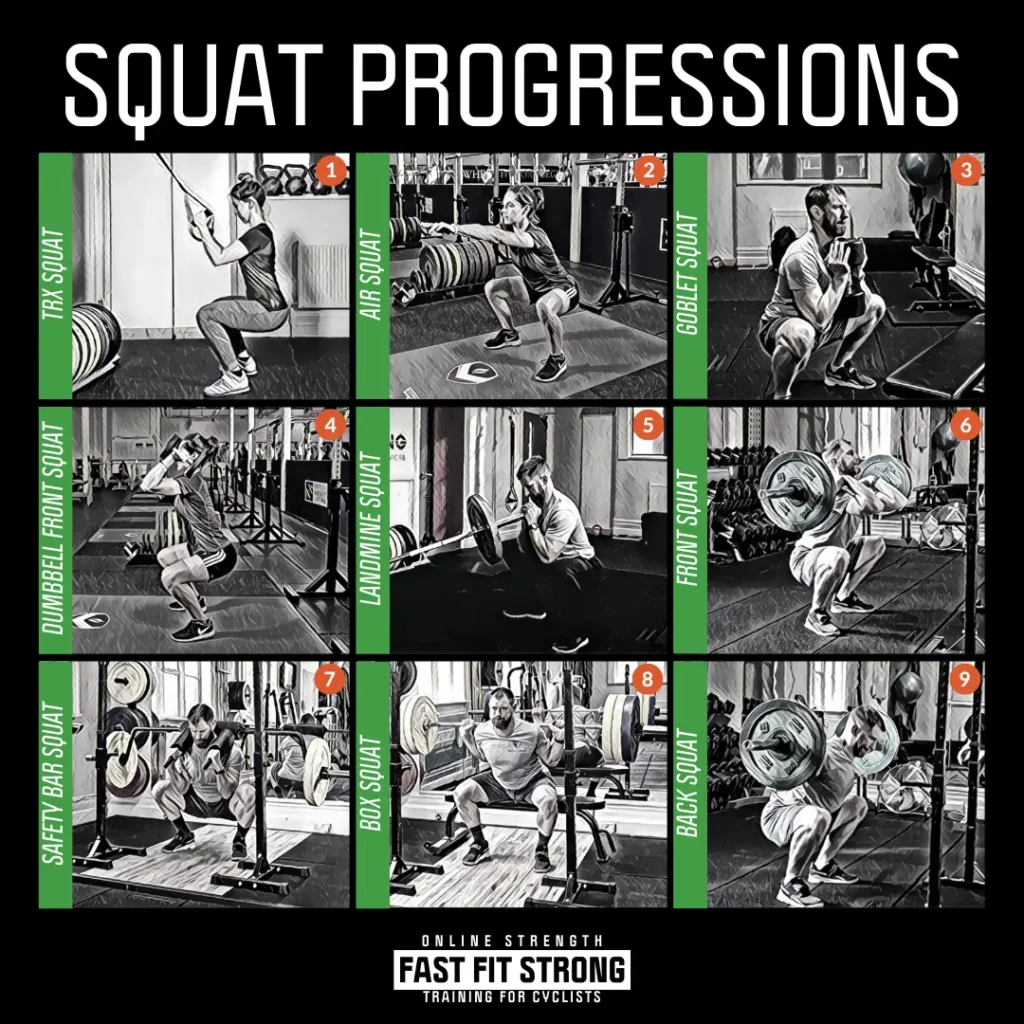

Squat Technical Progressions.

With complex, multi-joint movements like the squat, it’s a mistake to dive straight in with the most technically advanced exercise.

Instead, I like to build complexity through a series of technical progressions, so here is the route I use when teaching people how to squat:

- TRX Squat – This is great for a novice (or someone rehabbing an injury) because it reduces the load taken by the legs.

- Air Squat – Only using bodyweight and nothing else.

- Goblet Squat – My personal favourite. Because the weight is held in front, it’s a great way to learn the technique with a load.

- Dumbbell Front Squat – This can be very challenging and requires good upper-body and core strength.

- Landmine Squat – Similar to the Goblet Squat, but can be loaded much more than with dumbbells.

- Front Squat – Technically challenging (especially if you have stiff shoulders), but lighter loads make it a safer option for beginners.

- Safety-Bar Squat – Between a Front and a Back Squat, however not everyone has access to this kind of speciality bar!

- Box Squat – Sitting on a box gives a point of reference when starting out. Not one of my favourites, but can be useful under the right circumstances.

- Back Squat – The daddy! Done properly, this is simply the most effective exercise you can do in the gym!

When starting out, I think it’s very important to follow these technical progressions. It lets you improve your technique as you build up the weight. However, once you’ve got to the Goblet Squat, you can switch the order slightly if you like, but this is a great pathway to success!

How to do the Back Squat.

- Position a bar in a comfortable position behind your shoulders and stand with your feet slightly wider than shoulder-width, toes turned out slightly and chest upright.

- From here, transfer your weight towards your heels before bending your knees, keeping them pushed out wider than your ankles.

- The bottom position is when your thighs are horizontal. Your shins should be parallel with your spine.

- Stand by driving through your midfoot, aiming for your hips and shoulders to raise at the same speed.

How the Squat Transfers to Cycling

- Improved peak and sustained power; improvements in power have been shown everywhere between 30-seconds and over 3-hours.

- Improves inter and intra-muscular coordination, beneficial to the pedal action, especially at higher cadences.

- Evens stress through the knees, minimising the risk of anterior knee pain, which is extremely common in cycling.

Hip-Hinge (aka the Deadlift)

This is probably the most poorly executed movement by cyclists who venture into the gym, which is disappointing because when done well it has the potential to bulletproof your knees and back (two of the most common injury sites for cyclists), keeping you on the bike far more often.

The critical skill (and the thing most riders struggle with) is the ability to bend at the hip without compensating elsewhere. Two extremes are common:

- Firstly, locking out the knees and rounding the back like a question mark.

- Secondly, over-extending the lower back (as if wearing high heels) and bending the knees to lower the weight.

Both of these extremes are red flags and highlight the inability of most cyclists to control their own body movements!! They overwork the lower back (leading to pain) and underwork the glutes & hamstrings. However, once the basic technique is mastered, this is reversed, the glutes become the prime movers of the exercise and the lower back muscles are protected.

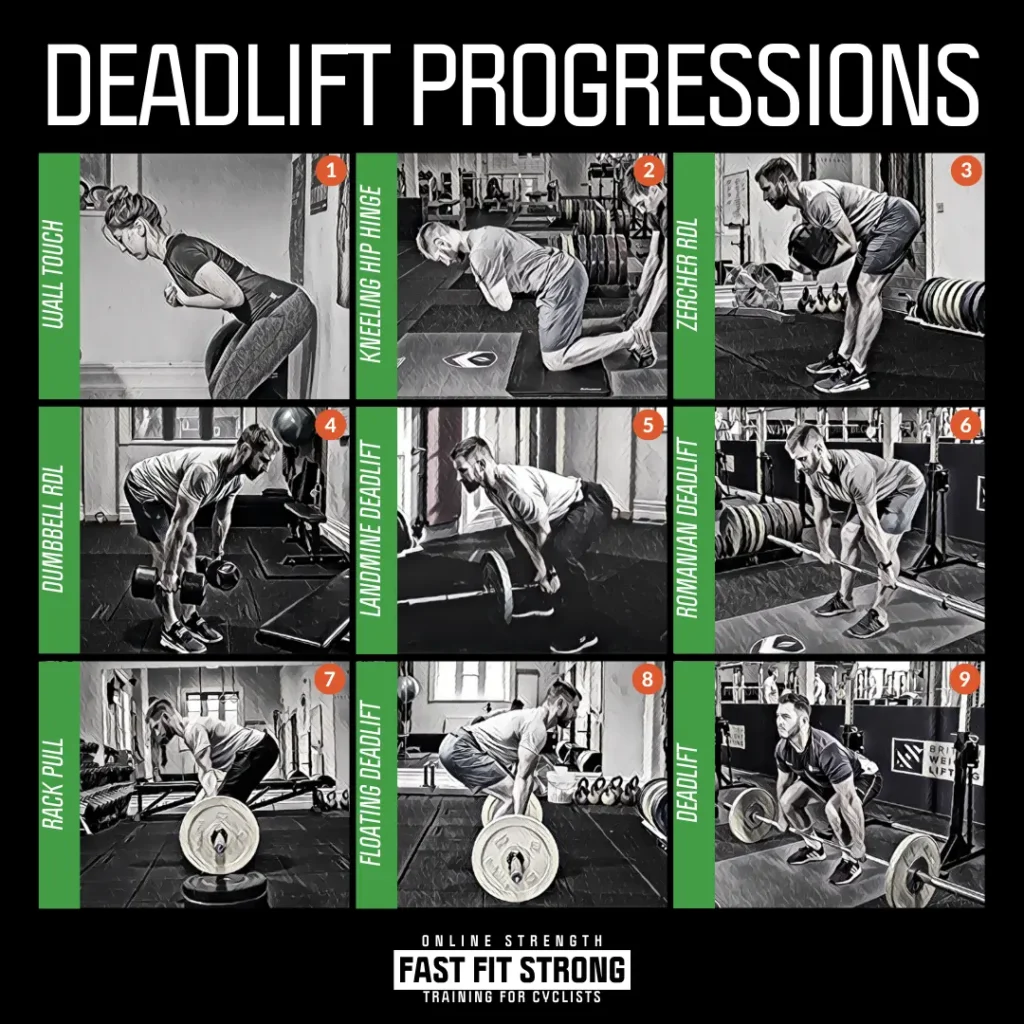

Technical Progressions for the Deadlift.

As mentioned above, the fundamental skill is the ability to freely hinge at the hip without compensating either through the knees or spine; once that is mastered, it opens the doorway to many other exercises and variations including kettlebell swings and Olympic lifts.

- Wall Touch – Mastering the Hip Hinge is an important first step to learning Deadlift patterns.

- Kneeling Hip Hinge – This challenges the Hip Hinge safely without loading the spine.

- Zercher Romanian Deadlift – Holding “soft” resistance like a sandbag across the chest challenges the Hip Hinge in a standing position, yet encourages a neutral spine.

- Dumbbell Romanian Deadlift – Once the hinging pattern is learned, you can progress to dumbbells. This makes it harder to keep your back straight, so is an important next step.

- Landmine Deadlift – This is a good option if you don’t have access to dumbbells or need to increase the load by smaller increments.

- Romanian Deadlift (RDL) – Progressing to the bar allows for heavier loads.

- Rack Pull – The first lift that introduces a “dead stop”, but limits the range of movement. Great for learning “pre-activation” to lift the weight off the rack.

- Floating Deadlift – Gradually increasing the range of movement.

- Deadlift – The full lift, from the floor with a dead stop. Second, only to the Back Squat, this is an important move in most of my programs.

It’s very important to follow these technical progressions, particularly up to the Romanian Deadlift, but once you can comfortably and consistently hip hinge, you can switch the order.

How to do the Deadlift.

The coaching sequence below is a general guide and the specific position that’s optimal for you will vary depending on your limb lengths and how they relate to the length of your spine.

- Take a hip-width stance in front of a bar.

- Push your hips back, creating tension in the backs of your legs, and take an overhand grip.

- Drive through your midfoot to lift the bar off the floor. Your hips and shoulders raise at the same speed.

- As you round your knees drive your hips forward to stand up and complete the lift.

- Reverse the action to lower the bar back to the floor in control.

How the Deadlift Transfers to Cycling.

- Promotes more efficient use of the glutes as prime movers and relegates the lower back extensor muscles to assistance muscles, adding power to the pedal stroke and limiting lower back pain.

- Disassociates the action of the hip from the knee and spine, minimising compensatory movement and allowing a more aggressive riding position.

- Promotes effective “pre-activation” allowing a more effective transfer of force through the kinetic chain.

- Heavier loads stimulate higher-threshold motor units, improving neural drive and making movements more efficient.

Horizontal Pulling

If getting cyclists to embrace the gym is difficult with lower body movements, getting them to adopt upper-body exercises is even harder, and I can understand the reluctance to add unnecessary weight and size to their upper bodies when power-to-weight and frontal surface area (CDA) are critical to riding performance.

But there’s a lot to be said for strengthening the upper body, not least when it comes to injury prevention.

Having poor posture with skinny, weak and brittle shoulders will not help you in the event of a crash or fall and you will more than likely spend prolonged periods of time off the bike if you’re unfortunate enough to do something like dislocating your shoulder.

Let’s address the issue of adding weight. Increasing muscle mass is a difficult thing to do and if you are combining strength training with high volumes of endurance-based training, it’s nigh on impossible!!

With that out of the way, let’s think about why upper-body pulling based exercises are a good idea…it’s posture, pure and simple.

Drawing a weight towards your body perpendicular to your spine (as opposed to a vertical pull, such as a pull-up), requires the muscles of your upper back to depress and retract your shoulder girdle, squeezing your shoulder blades together. This places your shoulder joint in a better, more robust position.

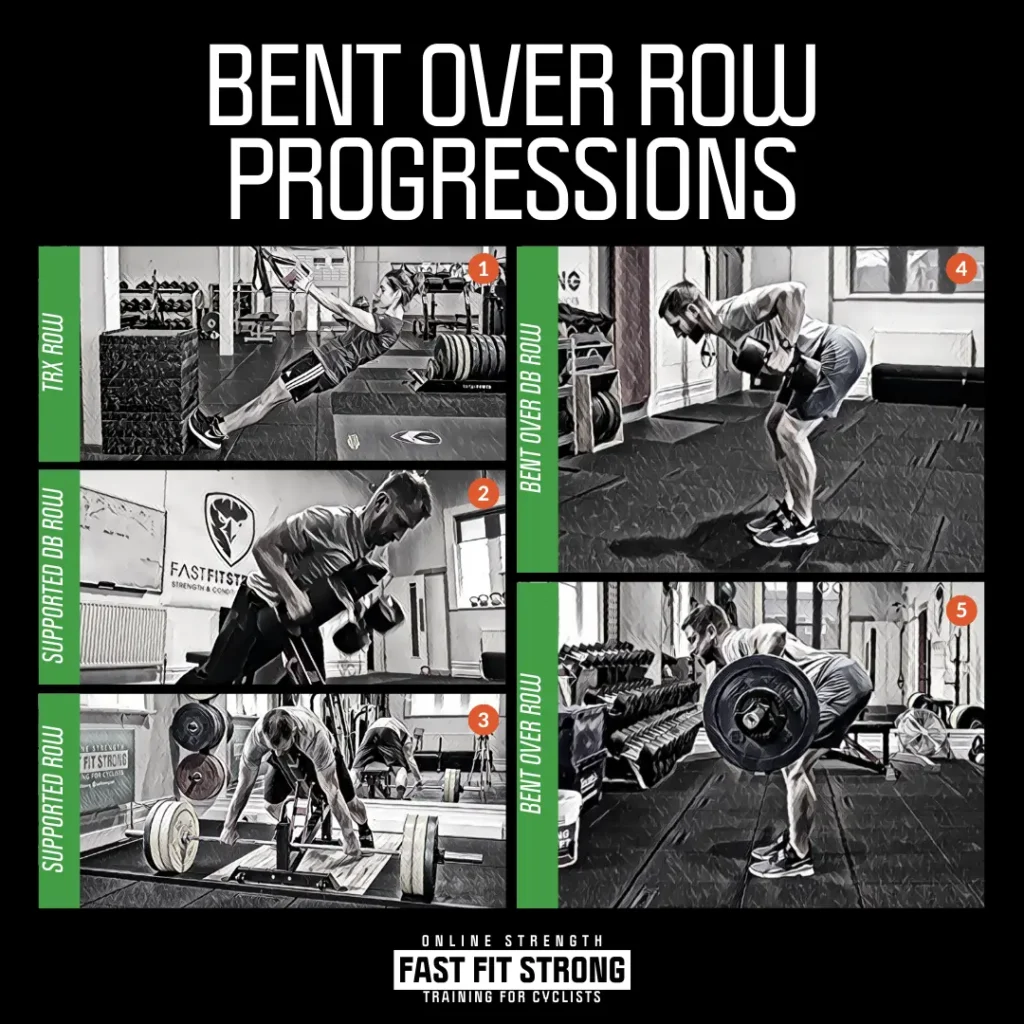

Horizontal Pull Teaching Progressions.

Although far less complex than the lower body moves described above, I still like to follow a technical teaching sequence when coaching people on how to perform horizontal pulling exercises. This allows for safe increases in load and volume as athletes learn to retract their shoulders, changing the exercise from an arm-dominant one, to one that’s controlled by their back and shoulders.

- TRX Row – This bodyweight exercise allows you to control the difficulty depending upon the distance of your feet from the anchor point.

- Chest-Supported Dumbbell Row – Using the bench as support, the risk of irritating the lower back is removed.

- Chest-Supported Row – More challenging than the dumbbell variation, heavier loads can be used, with finer increments.

- Bent-Over Dumbbell Row – Mastering the hip-hinge is necessary before progressing to this exercise, it’s essentially, the full technique but with lighter loads.

- Bent-Over Row – As with the dumbbell version, you need to be able to perform a good RDL before attempting this. Heavier weights with finer increments can be used.

It’s less important to follow the steps exactly as I’ve ordered them above. Once you’ve got the hang of pulling your shoulder blades together you can progress in more or less any order you like, with the exception of making sure you can perform a good quality hip hinge before either of the bent-over row variations.* note I often include single-arm variations (such as a dumbbell row or 3-Point Row) as separate, assistance exercises, but if you have limited equipment these are suitable alternatives.

How to do the Bent Over Row.

- Holding a bar with an overhand grip in front of your waist, lower your shoulders down by driving your hips backwards.

- From here, draw the bar towards your chest, making sure you keep a flat back. Your torso should stay still as you do this.

- Lower the bar in control before the next rep.

How the Horizontal Pull Transfers to Cycling.

- Improves posture thereby making the shoulder joint more resilient to injury.

- Better posterior strength helps improve the riding position, thereby minimising neck pain.

- Promotes coordination through the entire posterior chain, improving the coordination of the pedalling action, particularly the upstroke.

Horizontal Pressing

If there’s one move that’s overused by the general population and underused by cyclists it’s the horizontal press (ie the Bench Press) and while it’s the least important movement on this list, it’s still an important component of shoulder stability that you shouldn’t overlook.

I’ll reiterate the point I made above that it’s virtually impossible for cyclists to increase muscle mass due to the high volumes of endurance-based training you do, so you aren’t going to turn into a bodybuilder by doing this movement. I recommend it purely because it’s the most efficient way of stabilising your shoulder joints when done in combination with a horizontal pull.

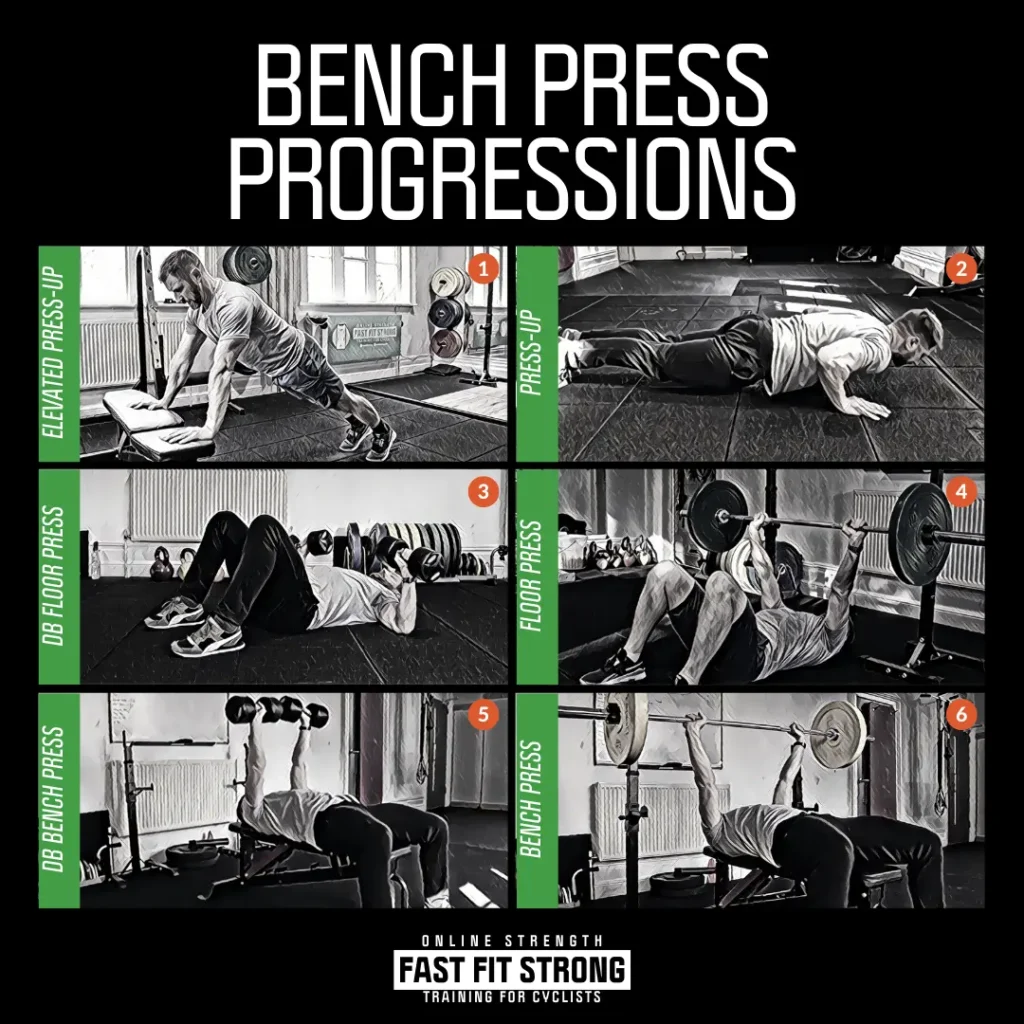

Bench Press Teaching Progressions

- Elevated Press-Up – Positioning yourself so that your shoulders are higher than your ankles reduces the load and makes the basic movement easier if you struggle to do full press-ups.

- Press-Up – If there was an easy way of loading this exercise I’d stop right here…all the benefits of the bench press but with the added bonus of needing to stabilise your trunk and avoid overextending your spine.

- Dumbbell Floor Press – Starting to add external load. Pressing from the floor reduces the range of movement, but allows you to control your hips and stabilise the weights.

- Floor Press – Progressing to a bar increases the weight you can lift, while also allowing smaller increments.

- Dumbbell Bench Press – Working from a bench means that your elbows can drop lower, thereby increasing the range of movement. Also, because your feet are now on the floor there is a greater need to control your posture and balance.

- Bench Press – As above, using the bar means heavier weights and smaller increments.

Unlike lower-body movements, using bodyweight only doesn’t necessarily make it easier. In fact, depending on your strength, the press-up could be one of the most difficult exercises on the list and certainly the most technically difficult to do efficiently.

It’s not unusual for me to mix up the order of the exercises, or even skip steps altogether.

How to do the Bench Press.

- Lay on a flat bench with your eyes directly underneath a straight bar.

- Select a grip slightly wider than shoulder-width apart, with your thumbs around the bar.

- When you’re ready, unrack the bar so that it is directly above your chest (nipple height).

- Lower the bar to your chest, touching it lightly, before pressing it straight back up again.

How the Horizontal Press Transfers to Cycling

- Works to complement the horizontal pull to cocoon the shoulder joint and limit injury.

- Helps maintain riding position, reducing aerodynamic drag and further limiting upper-body injuries including hand numbness and other neurological issues.

Bracing (aka Training the Core)

The “core” is one of those things in strength & conditioning that’s been bastardised beyond belief. For most people, it simply means your “abs”, but in actual fact, it’s much more than that…In sport (and in life), your core performs 2 functions:

- to protect your spine

- to transfer power through the body.

It does both of these things by preventing movement about your spine. As muscles like the Transversus Abdominis and Multifidus contract, they act as a cocoon around your spinal column.

Because life is 3D, it’s important to work in all three planes of movement – sagittal (anti-extension), frontal (anti-lateral flexion) and transverse (anti-rotation). In practice, this means resisting front-to-back, side-to-side and rotational movements (or combinations).

Whichever plane you’re working in, begin by contracting the deeper core muscles, known as “drawing-in” by sucking in your belly button towards your spine. Perform the exercise, making sure not to allow your trunk to move, twist or buckle and remember to breathe while doing the exercise!!

Anti-Extension Exercises.

The front plank is the go-to anti-extension exercise for most riders, but I feel it’s all too easy to slip into an anterior tilt and irritate your lower back. For me, a far better starting point is the deadbug exercise.

Here’s how to do it:

- Lay on your back with your knees directly over your hips and your shins parallel to the floor.

- From here draw in your core by pulling your belly button towards the floor and posteriorly rotating your pelvis.

- From here lower one heel to the floor, keeping the other where it is and not allowing your lower back or pelvis to change position.

- Raise to the starting position and repeat for the other side.

- As you improve; aim to increase the length of the lever by taking your heel further away, until you’re able to fully extend your leg without giving in to spinal extension.

Different anti-extension exercises are simply variations on the theme of holding your hips and spine in position while you move your limbs in various ways from various positions.

Deadbugs, Planks, Bird-Dogs and Hollow Holds are the broad categories I use. There are many, many variations within each one.

Anti-Rotation Exercises.

Resisting rotation through your spine (resist the twist) is critical for most sports as they incorporate a diagonal pattern of force (think a boxer planting his left foot to throw a right hand).

This includes cycling because the pedalling action places it under almost constant challenge. Every revolution, the left foot drives on the pedal, accompanied by an opposing pull on the handlebars with the right hand (and vice versa).

At the end of a gruelling ride, many cyclists lose the ability to control this and you’ll see their hips shifting from side to side (this is exacerbated if they have a poor bike fit and their saddle is too high!), which is one of the major contributing factors to lower back pain.

Anti-rotation exercises can be effectively paired with anti-extension exercises to form hybrid versions…most single-arm exercises do this (eg Single-Arm Bench Press), but my favourite movement is called the Pallof Press.

Here’s how to do it:

- Start in a half-kneeling position perpendicular to a band anchored at chest height; making sure that you limit anterior pelvic tilt.

- Without any compensatory movements, extend your arms straight forwards and backwards. The exercise should be smooth and fluid. Not jerky.

- Turn around and repeat the movement for the other side.

Anti-Lateral Flexion Exercises.

Finally, we come to resisting side-to-side movements. In my opinion, these are slightly less critical than the other two, but nonetheless still an important factor.

These mostly consist of variations of side-planks, but other options include loaded carries such as the suitcase carry or similar.

How to do the Side-Plank:

- Begin on your side, with your elbow directly under your shoulder.

- From here, raise your hips until there is a straight line from your ankles to your forehead.

- Additionally, don’t allow yourself to twist or buckle in any way.

- This can be made easier by lifting from your knees.

- Work for time.

- Turn over and do the same for the opposite side.

Conclusion

Cycling is a repetitive activity that leads to imbalances and overuse injuries, so it’s necessary to do something off-the-bike to counteract this, simultaneously undoing its negative effects, and boosting your ability to perform.

There are many options to choose from, but the most effective and time-efficient is resistance training which focuses on the fundamental movement patterns.

These movements can be difficult to learn, but their complexity is precisely why they are so effective.

Follow the coaching progressions I’ve provided for each of the fundamental movements and you’ll develop into a robust, powerful rider.

If you’d like more information on these moves, or even a fully thought out training plan that complements your riding, no matter your ability level, experience to time of the season, then I’d love to help you. That’s why I’m here!